WARNING

This article is intended to be a brief overview and not a comprehensive guide for treating bug bites and stings. If you think you might be having an allergic reaction or the bite/sting appears to be getting infected, seek medical attention.

The Great Outdoors is, well, great, but there’s always a chance you may run afoul of the creatures that live in it. Rarely, you may have an encounter with a bear, mountain lion, or rattlesnake. Much more often, however, you’ll encounter a hostile bug or a whole swarm of them. Off the grid, few people can say they’ve never had a bite or a sting from one of the wilderness’ smaller residents.

The scientific name for what we consider bugs is “arthropods.” Arthropods include insects (ants, bees, wasps, etc.) and arachnids (ticks, spiders, lice, scorpions, etc.). If a bug wakes you up at night by crawling across your face, the difference between them may not matter to you, but you should still know which is which.

The main differences between insects and arachnids are in how they’re built. Insects have three body segments (head, thorax, abdomen), while arachnids have just two (cephalothorax, abdomen). Insects have six legs, while arachnids have eight. Another difference is that insects have two antennae, and some have wings. Arachnids have neither.

Let’s discuss some of the most common offenders with regards to bites and stings.

Above: The mosquito is the world’s deadliest creature, believe it or not.

Mosquito Bites

What’s the most dangerous creature in the world? The great white shark? The Bengal Tiger? The grizzly bear? Nope. It’s the mosquito. Mosquitoes transmit various microorganisms that cause disease (pathogens) by acting as a carrier “vector.” That is, they don’t get sick themselves but pass infections to others through their bite. Mosquito-borne diseases include malaria, dengue fever, West Nile, yellow fever, Zika, and chikungunya. Malaria alone killed 627,000 people in 2020.

Only females bite humans. They have a long mouthpart called a “proboscis,” which pierces the skin, sucks out blood, and injects saliva into the bloodstream. This saliva can contain pathogens as well as allergy-causing substances (allergens). Although severe allergic reactions to mosquito

bites are extremely rare, individuals who are truly allergic may experience hives, swollen throat, and wheezing. The bite itself usually appears as a small, puffy lump that appears soon after you’re bitten. It will often turn red and cause itchiness for a time. Scratching is discouraged, as it can cause a skin infection. No treatment is necessary, although calamine lotion, hydrocortisone cream, or antihistamines can be used if needed. Signs of infection passed by mosquitoes may include fever, headache, and body aches. If these symptoms occur, further investigation is warranted.

Prevention involves removing possible mosquito breeding grounds from the area. Any area of standing water — even just an empty soda can or old tire should be removed. Mosquitoes are most active during warm weather, so repellents should be applied if spending time outside.

The most effective chemical repellents in the United States include one of these active ingredients:

- DEET

- Picaridin

- IR3535

- Para-menthane-diol (PMD)

- 2-Undecanone

- Oil of lemon eucalyptus

Whichever product you choose, read the label before you apply it. DEET may offer the longest-lasting protection. Other than lemon eucalyptus, plants and oils that discourage mosquitoes include rosemary, lavender, mint, lemongrass, and marigold. If you’re using a spray repellent, apply it outdoors and away from food. You may need to reapply it 6 to 8 hours later if you’re still in an area where mosquitoes are active.

There are situations where you might require both sunscreen and insect repellent. In these cases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend sunscreen first, wait until it dries, then apply repellent. It should be noted that sunscreen should be reapplied every two hours or so.

Other ways to prevent mosquito bites:

- When outdoors, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants. Tuck cuffs into your socks.

- Clothing (but not skin) can be sprayed with the insecticide Permethrin 0.5 percent.

- In primitive settings where air conditioning isn’t an option, use mosquito netting and door/window screens.

Above: Honeybees leave their stinger and part of their abdomen when they sting.

Bee Stings

Bees, members of the order Hymenoptera, are important pollinators that are essential for a healthy ecosystem but are territorial and defend their hives by stinging intruders. Africanized “killer” honeybees are even more so, defending a wider area and even following an offender for hundreds of yards.

When a honeybee stings, it leaves a barbed stinger in the wound. This proves fatal to the bee, as it leaves some of its organs with the stinger as well when it pulls away. Most of the time, symptoms include an instant, sharp burning pain at the site which turns into a red welt. Some swelling in the area is also noted. In most people, the swelling and pain go away within a few hours but the redness may last up to a week.

Rapid action will speed recovery. If the stinger is still in the wound, remove it immediately with a fingernail or even by scraping with a credit card. The faster it is removed, the faster symptoms will resolve.

Then, follow this procedure:

- Clean the bite with soap and water or an antiseptic.

- Use ice packs to reduce pain and swelling.

- Use topical hydrocortisone cream or an antihistamine to reduce swelling.

- Use calamine lotion or an antihistamine to relieve itching.

- Oral antihistamines like diphenhydramine are also an option for symptom relief.

Severe allergic reactions from bee stings occur more often than with mosquito bites but are still uncommon. Also known as “anaphylaxis,” you’ll see:

- Prominent skin reactions, including pronounced swelling, hives, and itching

- Flushed or pale skin

- Rashes that develop away from the site of the sting

- Shortness of breath

- Swelling of the throat or tongue

- A weak, rapid pulse

- Nausea and vomiting

- Dizziness or fainting

- Loss of consciousness

Treatment for anaphylaxis in adults involves the use of epinephrine 0.3 mg (adrenaline) injections (the pediatric dose is 0.15 mg). Auto-injectors such as the EpiPen are pre-dosed and simple to use. More than one injection may be required in some cases. Oral antihistamines, as used for minor sting symptoms, are generally too slow to effectively stop an anaphylactic reaction.

To avoid bee stings in areas where they are plentiful, consider these tips:

- Clear garbage and fallen fruit from the area.

- Avoid leaving open cans or cups of sweet beverages outside.

- Tightly cover food containers and trash cans.

- Avoid brightly colored clothing.

- Wear long pants and shirts.

- Avoid using scented soaps or anything with a strong scent.

- Use gloves when trimming vegetation near a hive.

If bees are swarming near you, stay calm, cover your mouth and nose, and quickly exit the area. Swatting bees may provoke them to sting.

Above: Unlike bees, wasps are predators.

Wasp and Hornet Stings

Wasps and hornets, also Hymenoptera members, are similar to bees in many ways, but there are differences. One is that, unlike bees, these insects have smooth stingers that aren’t left at the site of the sting. A wasp or hornet can sting multiple times without sacrificing its life. Another is diet wasps and hornets take nectar from flowers, but also prey on spiders, flies, aphids, caterpillars, ants, bees, and insect larvae.

How are wasps and hornets different? Hornets are a type of wasp but tend to be larger and have wider heads. Wasps like yellowjackets have very slender waists as opposed to hornets, which are built thicker and rounder in the mid-section. In addition, most wasps have only one set of wings, while hornets have two. From a behavior standpoint, hornets are more aggressive and inflict more painful stings. In rare cases, the toxin in hornet venom can be deadly, especially if there have been multiple stings.

A wasp or hornet sting appears as a red, raised welt with a puncture hole in the middle. You can expect instant sharp, burning pain at the site of the sting. Hives or welts may develop peak signs at about 48 hours and last for up to a week. As time passes, the area may swell and look darker red or bruised. In severe cases, anaphylaxis as seen in bee stings may occur. The treatment for both minor and major reactions is the same.

Prevention strategies are also the same as for bees, with the added suggestion of clearing animal feces or roadkill from the area. They attract flies, which are on the menu for wasps and hornets.

Above: Fire ants will swarm and attack if their nest mound is disturbed.

Fire Ants Bites and Stings

Invasive species of insects are widespread in many areas of North America. One of the most concerning in terms of injuries to humans and pets is the fire ant. Originally from South America, the fire ant — another stinging member of the order Hymenoptera — is now widespread throughout the Southern U.S. and has even been identified in California. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) estimates that costs related to fire ant control, damage caused to crops, and medical treatment approaches several billion dollars annually.

Fire ants are more aggressive than native ants, pushing out local native species. They produce visible mounds in open areas. When the mound is stepped upon, hundreds swarm in response to the threat and bite exposed feet, ankles, and legs of both humans and animals.

The fire ant is unusual in that it both bites and stings.

Once on your skin, it bites in order to hold its body in place. This bite is minimally uncomfortable, but then the ant uses a stinger on its abdomen to inject venom called “solenopsin” into the intruder. The pain from the sting feels like a burn (hence, “fire ant”) and can be excruciating. Unless removed, the ant will sting multiple times. Dozens of ants may be involved, causing a significant amount of venom to be injected.

The site of the sting swells into a red bump within hours. It may develop a pustule similar to a whitehead pimple in the first 24 to 36 hours, which, if scratched, can become infected and cause scarring. If left alone, the bumps disappear after three days or so. If infected, antibiotics are often necessary. Some people become allergic to the venom and, in rare cases, may develop anaphylaxis that requires the use of epinephrine to treat.

Treatment involves topical medicines like hydrocortisone cream or calamine lotion. Oral antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) are also helpful. Home remedies include a paste made from baking soda and water, aloe vera, or a 50-percent bleach solution.

Above: An adult tick feeding.

Tick Bites

Ticks, members of the order Ixodida, are well-known carriers (also known as “vectors”) of disease-causing organisms that affect humans, pets, and wildlife. In the United States, they’re responsible for even more vector-borne diseases than the mosquito. In extreme cases, they can be a severe threat to long-term health.

You might think of ticks as insects, but they are actually tiny eight-legged arachnids related to scorpions and spiders. The range for ticks seems to be increasing, ranging all the way from the East coast to the South to the Upper Midwest. The Western blacklegged tick covers the entire Pacific coast. Others are more regional, such as the Lone Star Tick, mostly found in (you guessed it) Texas.

Ticks survive by biting the skin of a host and extracting a meal of blood. Unfortunately, they also transmit various disease-causing microbes to humans and animals through their infected saliva.

The CDC recognizes more than 15, including:

- Lyme disease

- Anaplasmosis

- Tularemia

- Babesiosis

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

- Ehrlichiosis

- Relapsing Fever

Ticks don’t jump like fleas do. Usually, ticks spend their time in grasses and bushes, holding on with their back pairs of legs and latching onto passersby with their front pair(s). The larvae, which also bite, like to live in leaf litter. In inhabited areas, they can be found in shaded woodpiles, leaf piles, or tall grass.

To pass along a disease to animals or humans, ticks must first find their hosts by detecting smells, sensing body heat, or feeling vibrations from movement. When the tick latches onto its victim, its mouth parts pierce the skin and start extracting blood. Blood meals are required for a larva to continue its progress to adulthood.

Bites may be difficult to identify, but as the tick remains attached to the skin for a relatively long time, redness and swelling may exist. Some note a burning sensation. If the tick is passing the organism that causes Lyme disease (Borrelia), more than half will develop a tell-tale “bull’s-eye” rash known as “erythema migrans” that spreads as time goes by. Treated early, antibiotics like doxycycline and amoxicillin can eliminate the infection. If ignored, long-term consequences can occur.

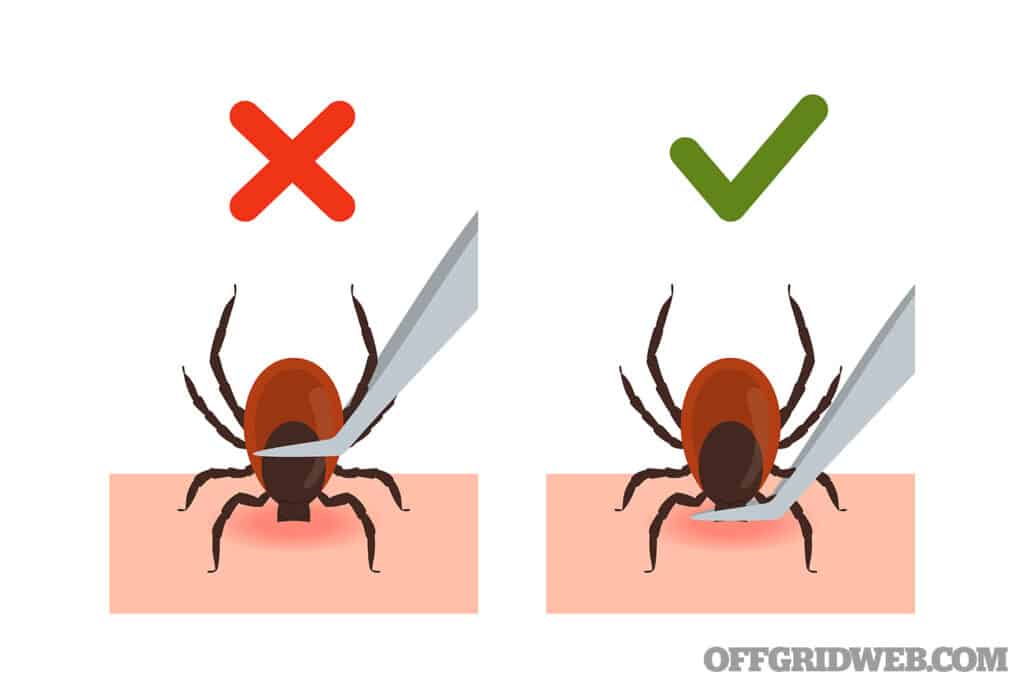

Once found, it’s important to remove the tick as soon as possible. It may be possible to just brush or wash it off if it hasn’t bitten you yet. If it’s deep in the skin, the simplest method is to use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the bug as close to the skin’s surface as possible and pull straight up in an even manner. Twisting as you pull or pulling at an angle may cause the mouth parts to remain in the skin.

After removal, thoroughly clean the wound area with soap and water or isopropyl (rubbing) alcohol and apply antibiotic ointment. Wash your hands afterward. As an added precaution, launder clothing in hot water and dry in high heat. If all this is done within the first day after the bite occurs, infection is highly unlikely.

Above: Pets and children should be inspected for ticks after a day outdoors. Grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible during removal.

For prevention, thorough exams after a day outdoors, paying special attention to children and dogs (especially their ears) In addition, consider:

- Long pants and sleeves in tick-rich environments

- Thick socks and high-top boots (tuck your pants into them)

- Walking in the center of trails to avoid brushing up against vegetation

- Using insect repellants like DEET (20 percent or greater) on skin (oil of lemon eucalyptus is one natural alternatives), as with mosquitoes

- Applying Permethrin 0.5-percent insecticide to clothing, hats, shoes, and camping gear 24 to 48 hours before using (proper application will even withstand laundering). Avoid use on skin, however.

Spider Bites

In temperate North America, two spiders are to be especially feared: The black widow and the brown recluse.

The black widow spider (genus Lactrodectus) is about ½-inch long and is active mostly at night. Southern black widows have a red hourglass pattern on the underside of their abdomens, but other sub-species may not. They rarely invade your home but can be found in outbuildings like barns and garages. Although its bite has very potent venom damaging to the nervous system, the effects on each individual are variable.

Above: Female black widow spider

A black widow bite will appear red and raised and you may see two small puncture marks at the site of the wound. Severe pain at the site is usually the first symptom soon after the bite.

Depending on the individual bitten and the amount of venom, you might see:

- Muscle cramps

- Abdominal pain

- Weakness

- Shakiness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fainting

- Chest pain

- Difficulty breathing

- Rapid heart rate

- Disorientation

Each person will present with a variable combination and degree of the above symptoms. The very young and the elderly are more seriously affected than most. Symptoms usually last for 3 to 7 days but may persist for several weeks.

Above: Brown recluse spider

The brown recluse spider (genus Loxosceles) has a tiny body and legs about an inch long. Unlike most spiders, it only has six eyes instead of eight, but they’re so small it is difficult to identify them from this characteristic.

Victims of brown recluse bites report them to be painless at first, but may experience these symptoms:

- Itching

- Pain, sometimes severe, after several hours

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

- Blisters

- Skin breakdown

The venom of the brown recluse is thought to be more potent than that of a rattlesnake, although much less is injected in its bite. Substances in the venom disrupt soft tissue, which leads to local damage to blood vessels, skin, and fat. This process, seen in severe cases, leads to death of tissue (called “necrosis”) immediately surrounding the bite. Areas affected may be extensive and take months to heal.

Above: Appearance of a brown recluse bite

Once bitten, the human body activates its immune response as a result, and can go haywire, destroying red blood cells and kidney tissue, and hampering the ability of blood to clot appropriately. These effects can lead to coma and eventually death. Almost all deaths from brown recluse bites have been recorded in children.

The general treatment for spider bites includes:

- Washing the area of the bite thoroughly with soap and water.

- Applying cool compresses to painful and swollen areas.

- Apply antibiotic ointment three times a day to prevent infection.

- Pain medications such as acetaminophen/Tylenol.

- Antihistamines for itching and swelling.

- Monitor on bed rest for severe symptoms.

- Raise an affected extremity.

- Warm baths for those with muscle cramps (black widow bites only; stay away from applying heat to the area with brown recluse bites).

- Antibiotics are sometimes prescribed to prevent secondary bacterial infections. Spider antivenom is sometimes given for black widow bites, much as snake antivenom is given for venomous snake bites. No antivenom is currently approved for brown recluse bites.

Above: The bark scorpion is common throughout the southwestern United States

Scorpion Stings

Most stinging bugs are insects, but an arachnid that can sting is the scorpion. Most scorpions are harmless; in the United States, only the bark scorpion of the Southwest desert (Centruroides sculpturatus) has toxins that can cause severe symptoms. Children are most at risk for major complications.

Although the bark scorpion is only 2 to 3 inches long, some scorpions may be much larger. They’re usually yellow to brown, have eight legs, eight eyes, and pincers, and inject venom through their “tail.” They’re most commonly active at night. Interestingly, scorpion exoskeletons are fluorescent under ultraviolet light, so you can find them most easily at night by using a “black light.”

Physical effects from scorpion stings often develop rapidly and affect the nervous system. Symptoms you may see include:

- Immediate pain in the area of the sting

- Swelling at the site

- Numbness or tingling

- Sweating

- Weakness

- Increased saliva output

- Vomiting

- Restlessness, twitching, or other unusual movements

- Irritability

- Difficulty swallowing

- Rapid breathing and heart rate

It’s important to act rapidly to treat a scorpion sting:

- Wash the area with soap and water.

- Remove jewelry from affected limb (swelling may occur).

- Apply cool compresses to decrease pain. A thin cloth between the skin and cold pack will decrease the chance of cold-related damage.

- Give an antihistamine, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl).

- Keep your patient calm and at rest; faster pulse rates speed the spread of venom.

- Limit food intake if the throat is swollen.

- Give pain relievers such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen but avoid narcotics — they may suppress breathing.

- Don’t cut into the wound or use suction to attempt to remove. It doesn’t help!

Symptoms tend to peak in the first few hours and resolve within a day. An antivenin is available that effectively treats children, the group most severely affected.

Final Thought

Off the grid, it’s important to watch out for the large predators, but it’s the smallest ones that can sometimes cause the most trouble. Know how to recognize them and treat their bites and stings.

About The Author

Joe Alton, MD, FACOG, FACS, is an actively licensed physician, medical preparedness advocate, and The New York Times bestselling author of several award-winning books, including The Survival Medicine Handbook: The Essential Guide For When Help Is NOT On The Way, now in its fourth edition. His website at www.doomand

bloom.net has over 1,500 articles, videos, and podcasts on medical and disaster preparedness, as well as an entire line of quality medical kits packed in the United States.

Read More

Don’t miss essential survival insights—sign up for Recoil Offgrid's free newsletter today!

Check out our other publications on the web: Recoil | Gun Digest | Blade | RecoilTV | RECOILtv (YouTube)

Editor's Note: This article has been modified from its original version for the web.

The post What’s Bugging You: Bug Bites and Stings appeared first on RECOIL OFFGRID.

By: Nick Italiano

Title: What’s Bugging You: Bug Bites and Stings

Sourced From: www.offgridweb.com/survival/whats-bugging-you-bug-bites-and-stings/

Published Date: Sat, 12 Oct 2024 11:00:09 +0000

------------------------

What is BushcraftSurvival SkillsToolsVideosBushcraft CampsBushcraft KitsBushcraft ProjectsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

What is BushcraftSurvival SkillsToolsVideosBushcraft CampsBushcraft KitsBushcraft ProjectsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions