Below is an event that actually happened to me. At the time of this incident, I’d been a mental health therapist for a few years, and after graduating and obtaining my license, had studied under Dr. Sal Minuchin for six months, one of the premier therapists of our lifetime. I was quite familiar with the fight-flight-freeze response that is hard-wired into our survival instincts. It is my hope that, as I walk through my thoughts and feelings as events unfolded, that you will be able to recognize what is going on and be able to find resilience during crisis.

The Scenario

I had eagerly anticipated this hike for months. It was to be my first exploration of Red Rock Canyon, and the scenery surpassed even the breathtaking images I had seen online. The vastness of the landscape had a way of humbling you, making you realize just how small we are in the grand scheme of things. The plan was straightforward – a couple of miles through one of the smaller foothill trails, then back.

Since I was unfamiliar with the area, I intended to stick to an intermediate trail. I set out early, well-prepared with a gallon of water and my survival kit. Another gallon waited in my vehicle for rehydration upon my return. The desert's reputation for quick dehydration isn't exaggerated; I found myself swatting away flies attracted to the moisture near my eyes.

Above: Becoming disoriented on a trail is a common way hikers become lost.

While soaking in the stunning views, I must have missed a turn in the trail. Suddenly, I found myself on a wild game trail. Lost in the moment, I had lapsed in judgment and strayed off the intended path without realizing it. The passage through the underbrush narrowed, signaling that I was clearly not on the trail meant for humans.

“Okay, no big deal,” I reassured myself. “I'll just retrace my steps.”

Despite my attempt at reassurance, panic lurked at the edges of my mind. Nearly half my water was already gone, and the thick brush hinted at hidden rattlesnakes. This was in the days before everyone owned smartphones, and even if I had one, it likely wouldn't have had a signal that far out.

Resilience Matters

As a Licensed Mental Health Therapist, the tables had turned. I now needed not only my survival training but also my mental health training to navigate this unexpected challenge. As I boy, I grew up raised by an 82nd Airborne Paratrooper who taught me wilderness survival, learned more survival skills in Boy Scouts, and was no stranger to hiking and camping.

“If anyone can figure this out, I can.” I thought. Or rather, tried to convince myself….

When we are faced with perceived danger, a part of the brain that is called the Amygdala gets activated, it sends signals to the Hypothalamus to activate the Sympathetic Nervous System. In Layman’s terms, this is your fight-flight-freeze response. When it is active, several things happen, your heart rate increases, your pupils dilate, your blood pressure increases, and your breathing becomes more rapid. If you are facing down a bear that decided that you look like a tasty snack, this would be helpful, because it makes your stronger, faster, and more resilient to pain.

Above: First Responders and Military personnel often deliberately place themselves into situations where they must conquer their fight-flight-freeze response.

But it also has some negative effects, the brain processing speed gets overclocked, your fine motor skills deteriorate, you can get tunnel vision, and the physiological responses in your body feel quite similar to a panic attack. Panic attacks can cause us to freeze or want to take flight, neither of which is good in a “lost in the wilderness scenario.”

In the same way that Soldiers and First Responders can train to manage that fight-flight-freeze response, so too can civilians learnt to apply training, including Hikers who get lost in a desert filled with rattlesnakes.

Understanding a little bit of mental health first aid can be life-saving skill for those who may encounter a personal emergency or who are trying to help calm someone who has just experienced a life-threatening scenario.

“Okay…” I thought, “let’s just backtrack a little. See if I can’t find the main trail.”

So, I walked about 10 minutes back down the game trail, and found several forks, most of which looked like more game trails, not hiking trails. Panic tried to creep in again.

“Sit down. Just sit down Sarge. Stop.” I thought.

S.T.O.P.

In all wilderness survival classes, they tell you that when you are lost, to remember the acronym S.T.O.P., an mnemonic acronym that stands for: Sit, Think, Observe, Plan.

YES, that’s it! What had I learned about being lost in the wilderness. STOP. Hug a tree. In this case, a desert boulder.

So as I sat there, I realized that my mind was racing, as was my heart, and that I had been dangerously close to panic-walking myself further into danger. I didn’t want to be one of those guys who panic walks in circles or further into the wilderness. That’s the thing with mental health first aid. Panic attacks can be mitigated, shortened, and in some cases eliminated with just a few skills.

As I sat on the boulder, I focused on my breathing, knowing that I needed to get my sympathetic nervous system under control first so I could make clear-headed decisions. Panic can be like an altered State of Consciousness. Some people get tunnel vision, most people get racing thoughts, and a few people get a de-realization/out-of-body feeling. None of the above is pleasant.

“Breathe.” I thought. “In through the nose, slow. SLOW. Hold it for a few seconds. Now release through the mouth even slower. Pause. Repeat.”

I did this for a few minutes until I started to feel a little calmer. Then I started working on my cognitions. The worst thing one can do is to think thoughts like “I’m gonna die” or “I’m really screwed.” These thoughts, and any catastrophic thinking really, such as “What if a rattlesnake bites me?” could trigger me right back into panic mode, because every thought we have. EVERY thought, has a biochemical response in the brain that causes a feeling/emotion, and this emotion, whether we all want to accept it or not, largely determines our behaviors and choices. This is the essence of cognitive behavioral therapy. Learning to control your thoughts, will improve your feelings, and this will help you make good decisions and choices. But it always starts with a thought, even a subtle one.

Above: Taking the time to think about your situation will help override the body's initial biochemical response to an emergency situation.

“Okay, what do we know?” I thought. “I know I can’t be too far off-course, no more than a couple miles. I know a few people knew generally where I was going (but not the specific trailhead) and that I expected to be back by nightfall. I know I have survival training and some kit with me that would help me make it through the night if needed. I can do this.”

My panic started to fade some more.

“Observe.” That was the next step right? Standing up from my boulder I looked around. The brush was too high in some areas to see far. That was a problem. I climbed a bit further up the foothill to find a spot that had a bit of an overlook. Looking down in the distance I could see what I thought was a road. Hard to tell in the desert because the sand and dust covers the pavement in some spots, but it looked right, and my instincts told me that was the general right direction I came from.

“Observe.” I thought again.

I started pulling things out of my pocket to see what I had with me. A pocket knife, a lighter, a small flashlight, a few bandaids, a small hank of cordage, a bit of jerky (trail snack), and about half a gallon of water left. I was wearing light, loose clothing, but my shirt was a shade of blue that was not normal for the desert landscape. It stood out. I also observed that I thought I had at least a couple hours of sunlight left based on the stacked fingers method against the horizon.

“Plan.” I thought finally. “Okay, if I head in that general direction, travelling down the foothills and to the South East, it should bring me to the road. From there, I might even see my vehicle, but if not, I can at least wait till the next car goes by and ask for a ride to the trailhead. If I find a large broken branch I can use it to tap the ground in front of me on these game trail, with a little luck I might not encounter any rattlers. But if I do, they may strike the stick first and I could use it to flick them away… maybe.”

Above: Thinking of, and preparing for potential dangers, such as aggressive wildlife, is an important step when trying to return to safety.

Supporting Others In A Crisis

It's likely that each of us will encounter emergencies in our lifetime, or maybe you will be the first responder for your family and neighbors in the aftermath of a tornado, or worse. People will be in panic mode. Anyone can learn to use some of these Mental Health First Aid skills to help others in these situations.

- First, determine that the scene is safe. If it is not, that must be your first priority, getting everyone to safety. Then, assess the group, find helpers, other people who do not seem to be in panic mode. Ask them to go check on other members of your group. Triage the situation, determine who needs your help first, then address that person by name. Assure them that they are safe now. Ask them to look around the area and tell you five things they see, four things they hear, three things they physically feel, two things they smell, and one thing they taste. It isn’t important that they get four things or three things, what you are doing is forcing them to input sensory information into their brain. This has a grounding effect.

- Next tell them to breathe slowly, in through their nose, out through their mouth. Really slow. Repeat for several minutes.

- Then ask them if they are okay, as them to describe what they witnessed and how it made them feel. This will help mitigate longer term effects such as nightmares or flashbacks to some extent. It’s not perfect, but this is Mental Health First Aid, not therapy.

- Validate their experiences, don’t argue with them, even if they saw something different than you. “You’re right, that was really scary.” Validation also will help mitigate the chances that the experience becomes something worse over time.

Above: In the midst of destruction, are people who need help mitigating their emotional trauma.

After The Crisis

The next step would be to prepare them for what is to happen next. “Ok, we’re going to try to get you to a hospital (or home if that’s appropriate.)”

You may tell them it is normal to be shaken up about the incident, and that they may even have bad dreams about it. If the dreams, or panic, or flashbacks (dissociative episodes) start happening and persist for more than a week, it might be a good idea to talk to a therapist for further help. But in many cases, the initial symptoms will fade over a week or so. The long term response depends on a lot of factors.

As a therapist who works with First Responders and Veterans, most of my patients have had a lot of experience with having to use that fight-flight-freeze response to survive dangerous encounters and to help others in danger.

While the training these individuals get for how to overcome the freeze-flight part of the response is excellent, many are not prepared for the long term after-effects of repeated activation of the Amygdala’s survival mechanism. Some people can be prone to long term panic attacks (or worse, nightmares, flashback dissociations, and more).

Any civilian can learn Mental Health First Aid. Search for classes on this in your area, it is often free and sponsored by trained professionals in the mental health community.

And if you are prone to panic attacks, (or worse symptoms) and find that some of the techniques described here are not helping to manage them, it may be a good idea to seek help from a licensed therapist.

Who will be prone to long term panic attacks is difficult to predict. There seems to be a genetic component, but it also has a lot to do with how we were raised, and that does not necessarily mean that being raised in a good environment or bad environment makes one more prone, but rather how we learned to think, how we believe the world “should work,” how we learned to problem solve, and what other life events we have already been exposed to. It’s not a matter of being weak or strong. In fact, some of the strongest soldiers, bravest fire fighters, most resilient officers, and most dedicated paramedics have come to see me in therapy for their symptoms. If anything, it takes great strength and bravery to ask someone else for help. It is not a weakness or character flaw.

Above: Knowing how to help guide someone through the stresses of a crisis can help mitigate some of the negative effects of traumatic events.

Conclusion

So what happened to Old Sarge? Well I made it down the foothill, mostly by sticking to my wits, and using the mental health skills that I had developed. Fortunately I didn’t need to spend the night in the desert, but if I had, I think I would have been ok too.

A few times on my descent the game trails got very narrow, and the brush so think that I could barely see my feet. I got pricked by more than a few cacti, but fortunately, no rattlesnakes!

Once I made it to the road, I could see my vehicle about 1/10th of a mile to the South of where I came out. Not too shabby, considering that I could not see above the brush for most of my descent. I was thirst though… if you ever go hiking in the desert, bring much more water than you think you will need.

I now teach mental health first aid and mental health awareness as part of my content on my YouTube channel, Prepping With Sarge, in hopes that it helps people manage their mind and emotions for the emergencies they will face.

I’ve not returned to Red Rock Canyon since that hike, but I hope to one day. I hope I can find the same trail, walk it again, and figure out where I went off course.

I do hike frequently still, but now I approach it differently. I always carry a survival kit of course, but now I make sure I tell someone EXACTLY where I am starting my hike, and when I expect to be back. I carry more water, and several ways to purify water. And most of all, I try not to get so overcome with the scenery that I lose track of the trail!

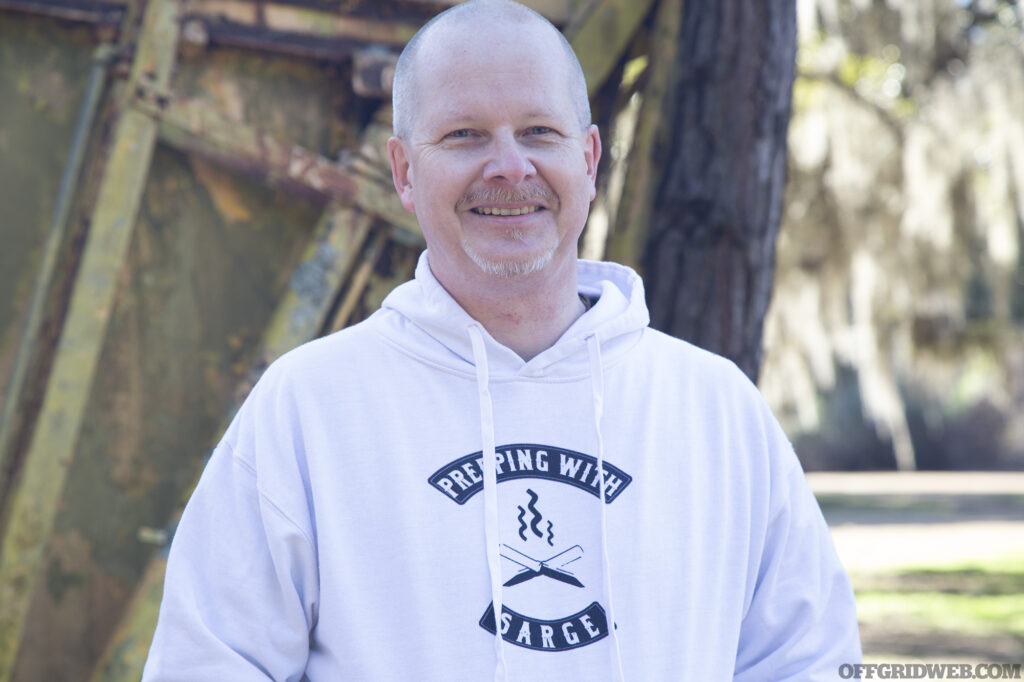

About Tom Sarge

Tom Sarge is a content creator for YouTube and Instagram under the channel name Prepping With Sarge, where he focuses on preparedness topics such as Mental Health First Aid, Wilderness Foraging, and Food Self Sufficiency. He also manages a Mental Health Channel on YouTube where he teaches people how to manage the effects of trauma, anxiety, panic disorder, and insomnia called The Official Mental Health Matters Channel. Currently he works as full time therapist for First Responders.

Read More

Subscribe to Recoil Offgrid's free newsletter for more content like this.

The post Resilience During Crisis: Managing Mental Health appeared first on RECOIL OFFGRID.

By: Patrick Diedrich

Title: Resilience During Crisis: Managing Mental Health

Sourced From: www.offgridweb.com/preparation/resilience-during-crisis-managing-mental-health/

Published Date: Mon, 26 Feb 2024 12:00:57 +0000

------------------------

Did you miss our previous article...

https://bushcrafttips.com/bushcraft-news/the-homemade-spam-recipe-you-need-to-try

What is BushcraftSurvival SkillsToolsVideosBushcraft CampsBushcraft KitsBushcraft ProjectsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

What is BushcraftSurvival SkillsToolsVideosBushcraft CampsBushcraft KitsBushcraft ProjectsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions