Opportunities, both good and bad, are everywhere for those who are paying attention. Pursuing a detrimental opportunity can lead to unfortunate events and an early demise. Taking advantage of the good ones can lead to a life pursuing passion and finding fulfillment. In the case of Michael Neiger, having the foresight to answer noble callings placed him in a unique position to help those who chose the latter. Over the span of his career in law enforcement and search and rescue, he has developed a unique skill set, and a powerful understanding of human nature.

Michael, now retired from the Michigan State Police, and founder of Michigan Backcountry Search And Rescue, spends his time searching for long-term lost and missing loved ones. This painstakingly difficult task often takes place in some of the most remote corners of the world, under the most extreme conditions the human body can endure. However, his passion helps bring closure to those suffering the agony of not knowing what happened to their lost family or friends.

Many cases that he has worked on have been featured in several books such as Where Monsters Hide: Sex, Murder, and Madness in the Midwest, by New York Times bestselling author M. William Phelps, and The Cold Vanish: Seeking the Missing in North America's Wildlands, by John Billman, just to name a few. His exploits have been highlighted in Outside Magazine, Explore Magazine, and Readers Digest. A regular speaker at outdoor symposiums throughout the midwest, his expertise and unique casework has found its way on the air on several media outlets like ABC’s 20/20, HBO’s Crime Watch Daily with Chris Hansen and many more.

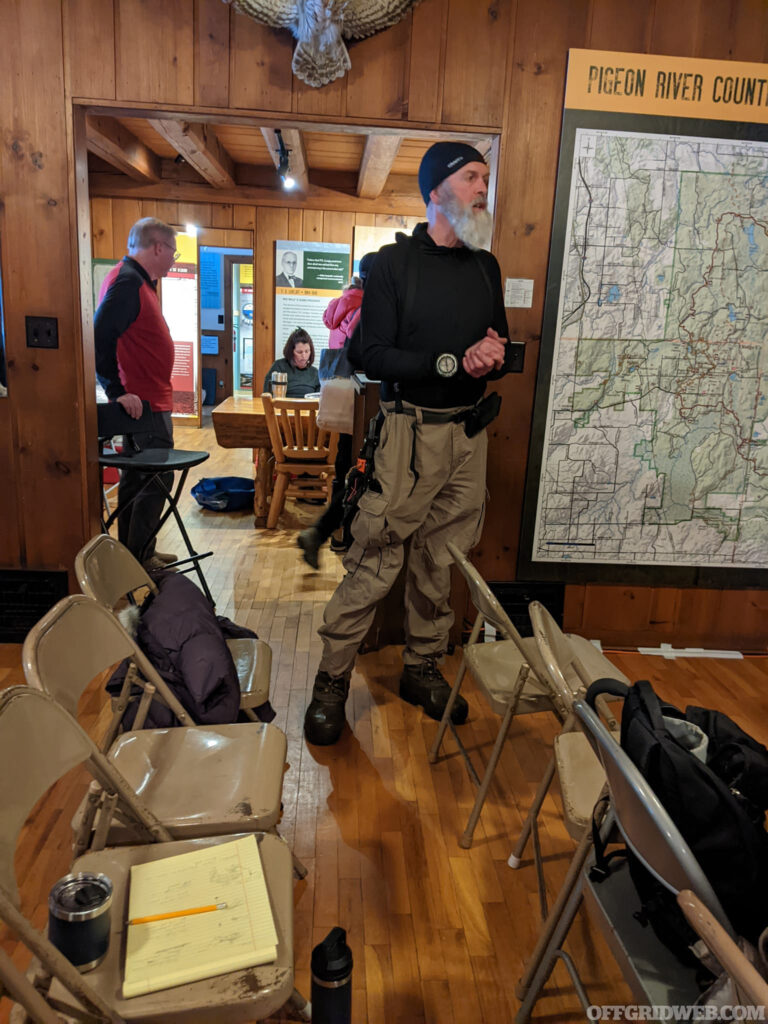

After attending a class on how Long Term Missing searches were conducted in the backcountry, we dug in a little further to learn more about his methods, the training he endures to perform optimally in the field, and what aspiring backcountry searchers can do to follow in his footsteps.

Interview With Michael Neiger

RECOIL OFFGRID: The wilderness has always been a part of your life because of your family’s passion for the outdoors. What key moments in your childhood helped kindle your own inner passion for outdoor adventure?

MICHAEL NEIGER: My parents took my older brother and I to the outdoors often. We were in the Boy Scouts, and my Dad was a Troop leader. He taught us how to hunt, fish, pick mushrooms, collect maple sap, build a fire, melt snow in the winter, camp, ski, snowshoe, and canoe. Each summer, he took us to his fishing camp, a two-story log cabin on a remote lake in the Canadian bush.

What attracted you to starting a career with the Michigan State Police, and how did your interests in Law Enforcement evolve over time?

MN: My Dad was an administrator at Northern Michigan University in Marquette, Michigan. He was charged with setting up educational programs, two of which were an associate, and bachelor degree in law enforcement. When he was interviewing and recruiting teachers for the program, they would come over to our house for dinner. During that time I was working as a mechanic on BMW motorcycles. Helping others and investigating crimes was more appealing to me, so I switched from a degree in industrial technology to one in law enforcement.

It takes a lot of stamina to go on arctic expeditions or search the wilderness for long-term missing, and you obviously work very hard to stay in peak physical condition. What does your favorite workout routine look like?

MN: While I have done a lot of trail running–including multiple 26-mile marathons, a 50-mile ultra marathon, and a 62-mile ultra marathon–I currently exercise daily, for 8 or 9 days in a row, before taking a rest day. My workouts usually last 45 to 60 minutes a day, and focus on cross-training and high-intensity interval training (HIIT): weight-lifting with free weights and machines, core strengthening, swimming, spinning, rowing, climbing a 40-degree Jacobs Ladder, ascending an inclined treadmill or stair climber, working on an elliptical trainer, and trail running. To complement this regimen, I try to eat and drink healthy, lots of protein, not so much sugar.

At what point did you make the decision to start working on Long Term Missing cases?

MN: A few years after retiring from my 26-year career with the Michigan State Police, I read about a man and his dog who went missing in a very remote, inhospitable section of Tahquamenon Falls State Park in the eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan. When the search was called off and suspended after two weeks of searching by first-line SAR teams and K-9 teams with no results, I offered my search and investigative services to the County Sheriff. This initial case led me to found Michigan Backcountry Search and Rescue (MibSAR) and its Long Range Special Operations Group (LRSOG) 15 years ago. Since then, I have worked on dozens of long-term missing (LTM) person cases, unsolved murders, and other cases, in the remote bush between the Upper Great Lakes in Michigan and Wisconsin, and the Arctic Ocean in Ontario, Canada

While serving with the Michigan State Police, what skills did you learn that you apply while conducting LTM searches?

MN: There are many skills that transfer nicely to LTM searches. Some of those include: crime scene searching; evidence documentation, collection, processing, and analysis; interview and interrogation techniques; observation; investigative techniques; report writing; crime scene drawings; courtroom exhibits; photography; testifying in a court of law, etc.

You have several guidebooks to remote locations. What inspired you to take on this endeavor, and did you start writing guide books before or after working on LTM cases?

MN: I started writing guidebooks to national and state parks immediately after retiring from my 26-year career with the Michigan State Police (MSP). I had done a lot of writing with the MSP, and really enjoyed the research and writing process. Having organized and guided 100s of wilderness trips and expeditions over decades, I decided to write about some of the more off-the-beaten-path natural gems I had come across.

For example, in doing the fieldwork for Exploring Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, I found and cataloged hundreds of little-known and seldom-visited caves in the backcountry of the Lakeshore. The biggest grotto is known as The Amphitheater. It has its own 49-foot waterfall, and is massive enough to hold around 2,000 people. Another book I am currently writing is: Exploring Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, and involves documenting a large number of old copper mines, pits, and associated mining works.

I have written other backcountry guides, including: Exploring Tahquamenon Falls State Park, Exploring Grand Island National Recreation Area, and Exploring Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore.

In addition to my finished guidebooks, I have completed the fieldwork for Exploring the Agawa Canyon in Canada, and am currently doing the fieldwork for a guidebook on the Seney National Wildlife Refuge.

How many LTM cases have you worked on, and how many have you been able to close?

MN: I have worked, investigated, searched, or consulted on dozens of cases, including around 100 in the United States, 13 in Canada, and one each in Mexico, Peru, and Columbia. The cases I work on are generally the hardest of the hardest, as the best of the best have already worked on them, so they are very difficult, if not impossible in many cases, to close. That said, I have found human remains on several LTM expeditions, and contributed to the closure of many other cases.

While I have worked on a few national and international cases, most of my work involves investigating long-term-missing (LTM) person cases and unsolved murders in the remote bush between the Upper Great Lakes in Michigan and Wisconsin, and the Arctic Ocean in Ontario, Canada.

If we define the success of an LTM case as either finding, or knowing definitively what happened to the missing subject, what are some of the greatest challenges faced that affect the outcome of a successful LTM case?

MN: At one time, about half my LTM cases were murders, which are infinitely more difficult to close, often because they may involve dismemberment, the destruction of human remains using chemicals or heat, or the concealment of remains at one or more clandestine burial sites.

LTM cases are also very challenging due to the passage of time, perhaps months, years, or decades. In many areas, seasonal conifer needle drop and deciduous leaf shed can eventually cover spoor – human remains, clothing, and other evidence – to a point where it is not visible to the naked eye. Ground-level growth, such as ferns, grass, moss, and lichen, can also obscure human remains and other evidence.

With the passage of time, scavenging insects, rodents, birds, and animals – especially the fox, coyote, wolf, and even bear – reduce human remains through consumption, disarticulation, and scattering.

What are some of the greatest challenges that Search And Rescue (SAR) operations will face that affect a successful outcome?

MN: The inability to gain access to tracts of private property is a big problem in some cases. Owners with criminal records, or those involved in nefarious activities, such as possessing stolen property, illegal drug operations, or conservation law violations, are often less than helpful.

On cases that are several years old, especially decades old, it is not uncommon for the entire case file, including search records, to have been lost, even intentionally destroyed.

As an independent investigator, who often works directly for loved ones of the missing – free of charge – it is often very difficult, if not impossible, to gain access to official reports and search records on the case, even when the search has been suspended for years or decades. It is not uncommon to have to comb through newspaper microfilm, search social media posts, and reinterview those involved in the case.

For someone who may be interested in getting involved in SAR or LTM work, where should they start and what kind of training should they seek?

MN: I recommend those interested in volunteering with a SAR team contact their local sheriff, as in many jurisdictions, he or she is charged with responding to search-and-rescue calls, and often maintains a volunteer SAR team.

Independent K-9 teams are very common in many areas too, and they need handlers as well as support volunteers. An internet search should identify K-9 teams in your local area. You could also contact a regional or national search dog organization, such as the National Search Dog Alliance (NSDA), to identify member teams in your area. www.n-sda.org

As for SAR training, the National Association for Search and Rescue (NASAR) has trainers all over the country who offer a wide variety of SAR classes, from beginner to expert level. www.NASAR.org

Training in wilderness first-aid, CPR, traditional map-and-compass land navigation, GPS use, wilderness survival, knot-tying, rope handling, man-tracking and sign-cutting, lost-person profiles, lost-person behavior, search strategies, evidence recognition and preservation, personal load-out, and FEMA's incident command system (ICS) are also important skill-sets SAR professionals need to master.

Which outlets (social media, publications, posters, etc.) do you think generate the greatest amount of awareness in a missing persons case, and how often does it generate useful intel?

MN: Social media is a very powerful means of getting the message out on missing persons' cases, both current and old. I design social-media-friendly missing persons posters for all my cases, upload them to the internet on my website, and then share them on Facebook. They get great reach this way, and accompanied by a good textual narrative, pop-up easily when keywords are searched, even years later. I also distribute hard copies of posters in areas relevant to an investigation, and they spread awareness, stimulate discussion, sometimes even tips.

After going on so many solo trips, many of them to the inhospitable arctic, were there any moments where you thought you wouldn’t make it back?

MN: One of the biggest threats I face in the Arctic Ocean bush is falling through a patch of weak ice that is concealed beneath drifted snow, since most of my expedition routes are along frozen rivers, pulling a heavily-loaded expedition sledge with snowshoes, just as the Cree First Nations people did back in the day.

I have been very fortunate to never have fallen completely through rotten ice. For some margin of error, I carry self ice-rescue picks readily available at all times, and also use a custom, 6-foot-long ice probe to monitor for changing ice conditions. One end has a steel chisel tip so I can chip at the ice to see how thick and solid it is. The other end has a hardwood tip so I can pound on the ice, and sound-it-out, to see if it is supported by water (solid sound is safest) or air, from dropping water levels (hollow sound is very dangerous).

What knowledge or skill sets do you attribute to your survivability during solo trips?

MN: When I started solo expeditioning 40-some years ago, GPS units were not available, and I had to be very careful with my map-and-compass work so I knew where I was at all times, and did not get lost in the expansive, road-less terrain.

Likewise, satellite rescue beacons were not available, except to pilots, and 2-way satellite messaging was a long way off, so I had to be very careful to avoid injury or illness, since I had no comms. Eventually I purchased an emergency locator transmitter (ELT) carried by pilots. They were illegal for me to use, but, if it saved my life, I was willing to pay the 4-figure fine.

Another thing that has helped me survive my expeditions is being in peak physical condition all the time, and spending countless nights in the bush beforehand. This allowed me to hone my wilderness skill-set to a high level of proficiency.

Lots of time in the bush has taught me how to gauge my hydration and fuel levels for maximum performance, while at the same time avoiding exhaustion. I also learned to thermoregulate by layering like an onion, doffing and donning layers as needed to avoid getting soaked from sweat, or dangerously cold and hypothermic.

What is your typical load-out for a solo arctic trek?

MN:

- Clothing worn while man-hauling sledge: thin wicking beanie and wide-brimmed boonie hat with ear flaps; thin wicking long-sleeve top with hoodie and wrist gaiters; thin wicking long johns with rip-off legs; thin liner socks inside vapor barrier socks inside thick wool socks; wind-proof over-parka with tunnel hood and wolf-fur ruff; wind-proof overpants; fingerless gloves; mitten shells with removable fleece liners, attached to web neck harness; sun glasses; bandana; watch; large wrist compass; breathable mukluks with moose-hide soles, frost plug insoles, thick wool felt insoles, and two nesting 9mm wool felt liners; butane lighter suspended from neck on shockcord to keep it warm and ready for use; bowie knife in drop-sheath with two pouches containing ice-rescue picks, toilet paper, and small channel lock pliers and multi tool on loss-prevention lanyard.

- Heavily-insulated clothing: two 1/4-inch-thick insulated jackets, one with hood; one pair of 1/4-inch-thick insulated overpants with full side-zips; one two-inch-thick insulated overparka with hood; one two-inch-thick pair of insulated overpants with full side-zips.

- Extra clothing: two pair of fleece mitten liners; wool felt mukluk insoles and liners; 3 pair of thick socks; 3 thin wicking tops; two thin wicking bottoms with full side zips; thin and thick balaclavas; insulated bomber hat; oversized rain parka and rain pants, rain mitts, rain cover for boonie hat.

- Transport: 12- by 60-inch Cree or Alaskan snowshoes; two big-basket ski poles; custom 6-foot-long expedition cargo sledge with cargo-retention straps and brush-guards so it does not snag on brush, pulled with chest-and-waist harness via 6-foot-long aluminum X-traces. Sled deicing kit (scraper and scrub pad). A chest-and-waist pulling harness has multiple pouches racked on both shoulder straps and the waist belt for ready access to snacks, water bottle (insulated pouch), compass, GPS, map, basic first-aid kit, extra hats and mitten liners, extra wicking T-shirt and long-sleeve top, pair of zip-off wicking bottoms, pair of heater insoles, thin micro-insulated jacket and pants with side-zips for exposure to high winds or colder temperatures.

- Communication gear: SARSAT-enabled Personal Locator Beacon (PLB); sat phone and rescue-and-evacuation insurance on some expeditions.

- Navigation gear: Brunton prism-sighting baseplate compass, custom Suunto baseplate wrist compass; UTM roamer corner plotter; ranger pacing beads; primary topographic maps; waterproof notepad; pencil; waterproof pen; dental floss for distance measuring on map.

- Hydration system: two heavy-duty one-liter Nalgene water bottles; two heavily-insulated water bottle parkas; one 20-ounce insulated thermos for hot lunch.

- Ice-rescue gear: two ice-rescue picks are carried in a pouch on drop-sheath bowie knife; one climbing-grade carabiner; 6-feet of tubular webbing for anchor sling; 50-feet of floating rescue-grade rope in throw-bag mounted on front of sledge for rescue, and rigging belay or hall system in steep terrain; and a custom, 6-foot-long ice probe to monitor for changing ice conditions.

- In-pockets/on-person survival gear (not in sledge or on removable hauling harness): lock-blade pocket knife; magnesium tinder rod; ferro sparking rod and scraper/striker for magnesium and ferro rod; adjustable-flame butane lighter; water-proof fire-starters; wind-proof and waterproof lifeboat matches; pealess whistle; signal mirror; large rip-proof emergency blanket (shelter and signal panel); high-quality button-size compass; high-quality single-AAA aluminum flashlight; and map of area of operation.

- Ration cooking system: custom continuous-burn Trangia alcohol stove; multiple aluminum Sigg fuel cells for alcohol; stove float and windscreen; adjustable-flame butane lighter; one two-liter titanium cook pot with lid and campfire bail; pot holder; dipper cup; spoon; insulated mug with lid; and insulated food container with lid.

- Rations: 4,000 and 7,000 calories of rations per day, or about 2.5 to 3 pounds of food. Breakfast: granola; pound cake bar; vitamins; coffee or tea. Snacks: two liters of electrolyte drink mix; chocolate bars; granola bars; mixed nuts. Lunch: ramen soup; beef jerky; cheese; pilot biscuits; jam; cookies. Dinner: freeze-dried meal; pilot biscuits; jam; cheese; cookies.

- Spare equipment: extra batteries for flashlight and GPS; backup set of topographic maps; toilet paper; 9-hour candles.

- Repair parts and equipment: 50-feet of 1/8-inch-diameter lashing cordage; small roll of duct tape; small coil of wire; snowshoe binding hardware; sledge trace attachment bolt; sewing kit; small channel lock pliers and Leatherman multi-tool.

- First-aid equipment: Ace bandage; butterfly bandages; mole foam; moleskin; bandaids; gauze pads; roll bandage; first-aid tape, Israeli bandage; pain medicine; antibiotic; anti-inflammatory medicine; tweezers and scissors in pocket knife; cold, flu, and allergy medicine; diarrhea medicine.

- Bivouac equipment: snow shovel; 10-by-10 foot sil-nylon tarp, pre-rigged with cordage; short and long closed-cell insulating ground pads; snow-proof bivy sack; minus 60-degree Fahrenheit sleeping bag; vapor barrier liner for sleeping bag; 9-hour candle; single AAA lithium battery aluminum LED flashlight mounted on head strap; wood saw; and fire starters.

- Hygiene: small toilet paper roll in plastic bag; hand sanitizer; toothbrush; tooth powder (does not freeze); tooth picks; dental floss; and small pack towel.

How has your load-out changed over time, and what caused you to make those changes?

MN: The main changes I've been forced to make to my load-out were for weight reduction, simplification of processes, and improvements in reliability.

The weight of an Arctic Ocean kit is critical, since I have to man-haul it on a 6-foot-long expedition cargo sledge, often in up to 4 to 6 feet of powder snow, wearing huge, 12- by 60-inch, high-float Cree or Alaskan snowshoes. Add in negotiating semi-mountainous terrain tangled with brush and blowdowns, and every ounce counts. So, I am constantly looking at my kit, lightening it as best I can. Sometimes modifying an item helps reduce weight, or just replacing it with a new one if it can’t be changed.

Operating at ambient temperatures of minus 30- to 50-degrees Fahrenheit – much lower with windchills – means you only have a short period of time, sometimes measured in seconds, to use your fingers, before you need to tuck them back into your plunge mitts to rewarm them. This means every process must be as simplified as possible to reduce the number of steps or complexity, such as lacing one's snowshoes, rigging a shelter, lighting a stove, or preparing food. If your fingers get too cold, you will not be able to do any of these critical tasks, and being unable to light a fire or zip up a parka could result in a slow death.

Trying to fix a piece of equipment in windchills approaching triple digits is also extremely difficult, so every piece of an Arctic Ocean kit needs to be bombproof. In deep, subzero cold, everything must be very reliable, and easily field maintainable if it goes down.

How do you sustain yourself during your trips without resupply, and how long can you keep yourself going with your methods?

MN: My Arctic Ocean expeditions are usually limited to two weeks or less due to the weight of rations and fuel. On arduous expeditions in deep cold, I usually carry between 4,000 and 7,000 calories of rations per day, or about 2.5 to 3 pounds of food per day. To melt snow into water, and then boil it, requires about 10 ounces of fuel per day. So, two-weeks would mean man-hauling about 35 to 42 pounds of rations, and about 9 pounds of fuel, and that does not include 48 hours of backup rations and fuel.

If someone with no skills in wilderness trekking wanted to start, what skills should they master beforehand?

MN: Map-and-compass land navigation skills are essential, as is proficiency with a global positioning system (GPS).

Carrying an in-pockets survival kit (not in a rucksack or sledge, but on their person, in case they get lost), and proficiency with using each item, is very important, especially if you are traveling alone, and off-trail. For me, this includes: a bowie sheath knife, lock-blade pocket knife, magnesium tinder rod, ferro sparking rod, scraper/striker for magnesium and ferro rod, butane lighter, water-proof fire-starters, wind-proof and waterproof lifeboat matches, pealess whistle, signal mirror, large rip-proof emergency blanket (shelter and signal panel), high-quality button-size compass, high-quality single-AAA aluminum flashlight, and map of area of operation.

Since they need to be very familiar with how their body reacts to arduous wilderness tripping, as well as how to use and maintain their kit, adventurers should spend as much time in the bush – in foul weather, not fair weather – as they can, prior to any remote trek. A cold-weather survival class would also be very helpful, as would knowledge of wilderness first aid.

Clothing-wise, adventurers should avoid cotton clothing at all costs, even blends. Since it kills when wet – rapidly sucking the heat out of anything it comes in contact with – I call it the ‘Devil's Cloth'.

The key to operating in austere environments in very foul weather is having a rain parka and rain pants that are oversized, big enough to fit over all your layers, including your insulating layers. In addition, adventurers should have multiple thin layers of head-to-toe polypro wicking layers, all large enough to wear together in the worst conditions. Additional, roomy, insulating layers would then be worn over the wicking layers, and under the rain parka and pants.

Another key to successful wilderness tripping is being able to doff and don layers at will, fine tuning your layering system to the weather and workload you are facing at the moment, and when it changes. Layer like an onion.

Having a partner and some iron-clad means of communication with the outside world – such as a SARSAT-capable personal locator beacon (PLB) and a satellite phone – would also be recommended, as would rescue and evacuation insurance.

When you present or teach, what are the answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about what you do, and how you prepare?

MN: People often want to know how I stay alive on a remote expedition in deep-subzero cold – without a fire. The key is preparation and execution. I train hard so I am in peak physical condition for expedition; stay well hydrated and fueled-up; and dress like an onion, doffing and donning wicking, insulating, and shell layers to avoid becoming too hot (and sweating up my clothing) or becoming dangerously cold.

When you are teaching an outdoor skills class, what are some of the most common mistakes you see people making when they are trying to learn a new wilderness skill?

MN: Starting a fire is a huge challenge for those who are not skilled at it. Especially firewood selection and processing in a field setting without a saw or axe, particularly in foul weather. I teach them to carry a stout bowie knife, and then show them how to split lengths of wet wood to get at the dry heartwood using a bowie knife and a baton.

What is your advice to the friends and family of someone who has been missing for a long time?

MN: Read the Missing-Person Sourcebook. After having worked with so many loved ones of the missing or murdered, I authored the Missing-Person Sourcebook: A How-To Manual for Families Searching for a Missing or Murdered Loved One – Best Practices from the World's Top Experts. This huge, 22-chapter compendium of expert info is written specifically for families with unresolved cases, and it is free, online, at www.TinyURL.com/MPsourcebook.

They should search for volunteer K-9 search teams in their region, as they are often looking for cases to work on.

They should also make sure their missing loved one is listed in the US National Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs) database at www.NamUs.gov. They can start this listing themselves, and then solicit the help of the law enforcement agency with jurisdiction over their case to get their loved one's DNA sample entered into the FBI's CODIS database. This process will assist authorities across the county, and beyond, in matching family DNA samples with those of the missing and unidentified, no matter where they went missing or are found.

What are some common mistakes people make that get them killed in the wilderness?

MN: Getting lost or injured, and then succumbing to hypothermia (becoming too cold), hyperthermia (becoming overheated), dehydration (running out of water), often due to a lack of survival gear and proper insulating clothing in a daypack.

What are the most important steps people can take to prevent them from becoming a missing person?

MN: Always tell someone where you are going, etc. Use this hardcopy itinerary form I put together at www.MibSAR.com/classes/itin.pdf or download this itinerary app at www.AdventureSmart.ca

Always carry survival gear in your pockets, in case you get separated from your daypack.

Always carry a daypack lined with a large waterproof garbage bag containing insulating layers, rain gear, water, snacks, torso-length ground pad, large emergency blanket for shelter, metal cup for melting snow or boiling water; small saw, fire starters, lashing cordage, etc.

Carry a map, compass, and GPS unit, and learn how to use them beforehand.

Carry a Personal Locator Beacon (PLB), which will activate the satellite-based SARSAT-COSPAS international rescue system (the same system that provides authorities with the GPS coordinates for a plane when it crashes anywhere in the world).

How can people improve their situational awareness and decision making to help prevent them from becoming a missing person to begin with?

MN: To avoid poor decision making, always stay well hydrated and fueled-up, and never allow your body to get dangerously cold or hot. Always try to travel with a partner, and then monitor each other for signs of hyperthermia, hypothermia, and dehydration.

To learn more about wilderness tripping, read as much as you can, both in books and online; watch YouTube videos from experts; take classes; and find an experienced mentor. And then get outside as much as you can, starting locally, not venturing far from your vehicle, until you have learned the necessary wilderness skills for your desired outdoor activity.

About Michael Neiger

Hometown: Marquette, Michigan

Education: Ph.D. – Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science (Public Policy)

Childhood Idols: Frontiersman and soldier David Crockett – King of the Wild Frontier

Recommended Reading List:

- Ultimate Navigation Manual: All the techniques you need to become an expert navigator, by Lyle Brother

- Mountain and Moorland Navigation, by Kevin Walker

- Essential Wilderness Navigation: A Real-World-Guide to Finding Your Way Safely in the Woods With or Without a Map Compass or GPS, by Craig Caudill & Tracy Trimble

- Man Tracking in Law Enforcement, by David Michael Hull

- Fundamentals of Mantracking: The step-by-step method, by Donald C. Cooper and Albert “Ab” Taylor

- Bushcraft: Outdoor skills and wilderness survival, by Mors Kochanski

- Bushcraft 101: A field guide to the art of wilderness survival, by Dave Canterbury

- The SAS Survival Handbook: How to survive in the wild, in any climate, on land or at sea, by John ‘Lofty’ Wiseman

Favorite Movie: Black Hawk Down

Favorite Drink: Muscle Milk Protein Shake

Favorite Quote: Seek not the wilderness trip of a lifetime, but a lifetime of wilderness tripping!

Law Enforcement/SAR Experience:

- 26 years with Michigan State Police (Det/Sgt)

- 15 years with Michigan Backcountry Search and Rescue's (MibSAR) Long-Range Special Operations Group (LRSOG), (Founder and Lead Investigator)

- Certified as a SAR TECH 1 and Crew Leader by the National Association for Search and Rescue (NASAR)

URL/Social Media:

EDC Gear

(In-pocket survival gear when in the bush)

- Variable-flame, see-through butane lighter (Scripto)

- Windproof, waterproof lifeboat matches (UCO Stormproof Match Kit)

- Ferro sparking rod (Bushcraft Outfitters 3/8- by 4-inch Firesteel)

- Scraper/striker (FireSteel Super Scraper)

- Waterproof fire-starters (S.O.L. Tinder-Quik)

- U.S. Military Magnesium Tinder Bar with built-in ferro rod (Doan Machinery and Equipment Co)

- Machined-aluminum button compass with 24/7 tritium micro-light modules (Cammenga Tritium Wrist Compass J582T)

- Map of area

- LED flashlight with single-AAA lithium battery (E01 V2.0 AAA Fenix Flashlight)

- Pealess plastic whistle (Fox 40 Classic )

- Signal mirror (UST StarFlash Micro Signal Mirror)

- Rip-proof emergency blanket (2-person S.O.L. Survival Blanket)

- Pocket knife (Outrider Swiss Army Knife by Victorinox)

- Bowie knife (Fehrman Extreme Judgement, belt-mounted drop-sheath knife)

Read More

The post Michael Neiger: Heeding the Call, A Journey into the Wild appeared first on RECOIL OFFGRID.

By: Patrick Diedrich

Title: Michael Neiger: Heeding the Call, A Journey into the Wild

Sourced From: www.offgridweb.com/preparation/michael-neiger-interview/

Published Date: Sun, 10 Sep 2023 11:00:49 +0000

------------------------

Did you miss our previous article...

https://bushcrafttips.com/bushcraft-news/so-is-honey-flammable

What is BushcraftSurvival SkillsToolsVideosBushcraft CampsBushcraft KitsBushcraft ProjectsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

What is BushcraftSurvival SkillsToolsVideosBushcraft CampsBushcraft KitsBushcraft ProjectsPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions